Sami Bukhari and Eyal Danon’s installation (1) simulates the interior of a house in Jaffa, acquainting the viewers with the family of Nahle Chacar, one of the founders of Al-Rabbita, the League for the Arabs of Jaffa. The house in Jaffa, which is under Palestinian ownership, is presented in the context of contemporary Palestinian identity and culture, thus undermining the exclusive nature of the Jewish real-estate dream in Jaffa, raising the question: whose home Jaffa is.

The Architect’s House Gallery is located in Old Jaffa, in a building rented by the Israel Association of United Architects from the Orthodox Philanthropic Society in Jaffa. The Gallery has situated itself in Jaffa, as part of a Jewish mental map devoid of Palestinian sites. It features mainly Jewish-Western-Israeli architecture. Hence, the exhibition “A House in Jaffa” is an attempt to deviate from the Gallery’s hegemonic cognitive environs, and relate to another national culture existing in its close physical vicinity.

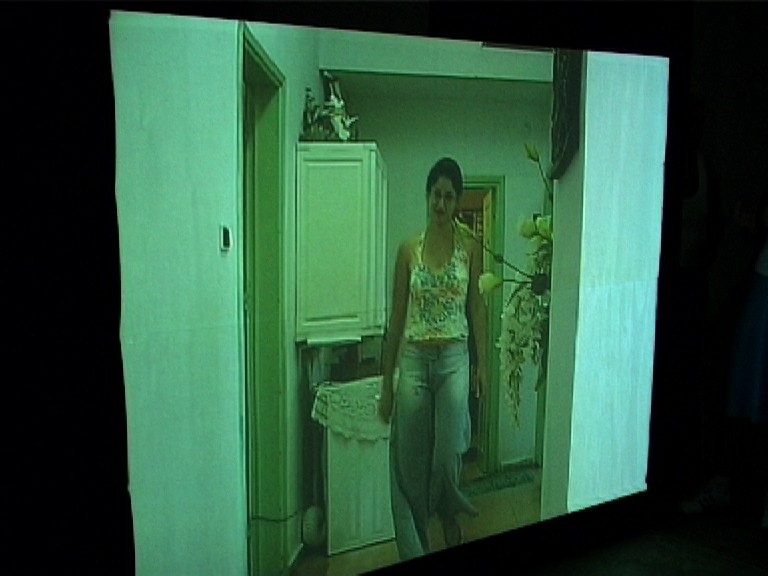

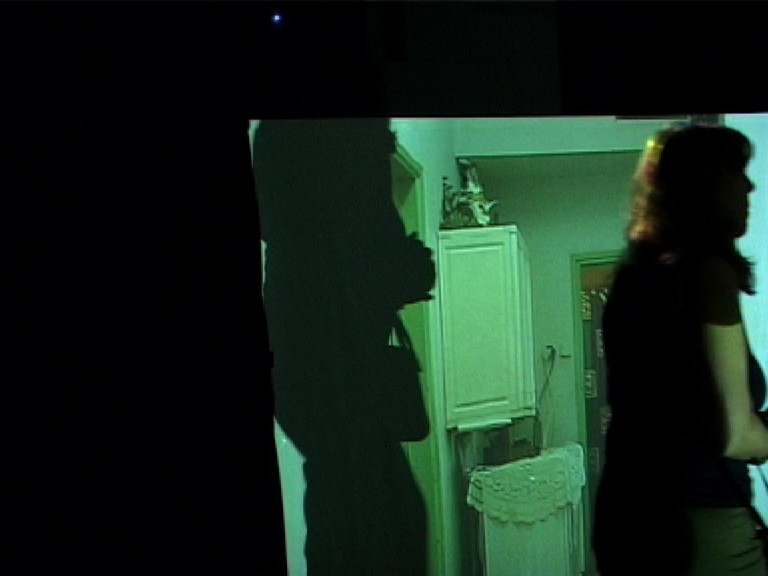

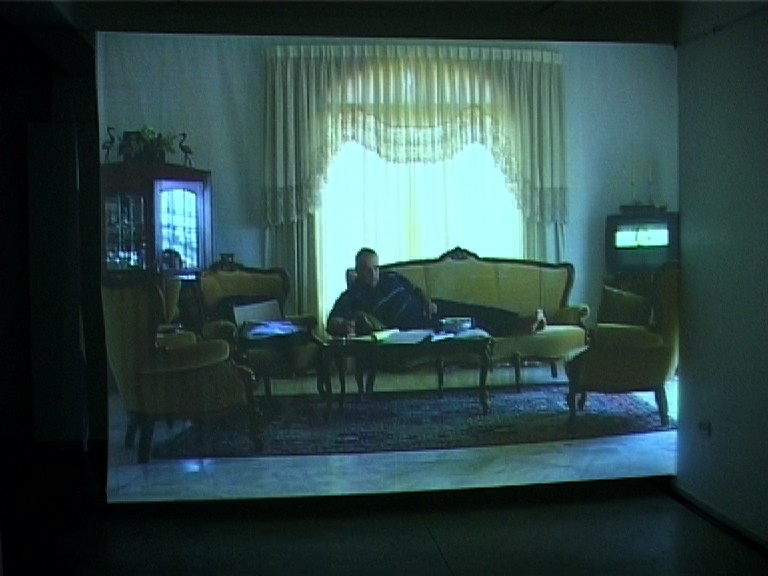

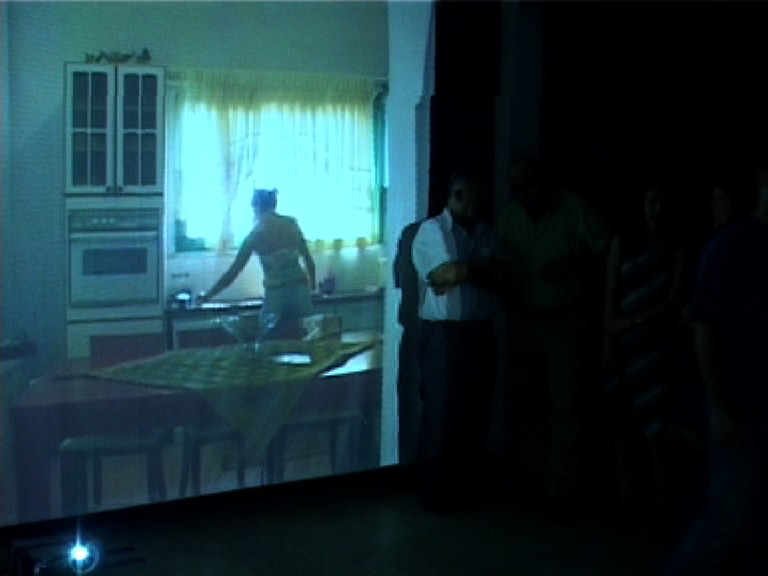

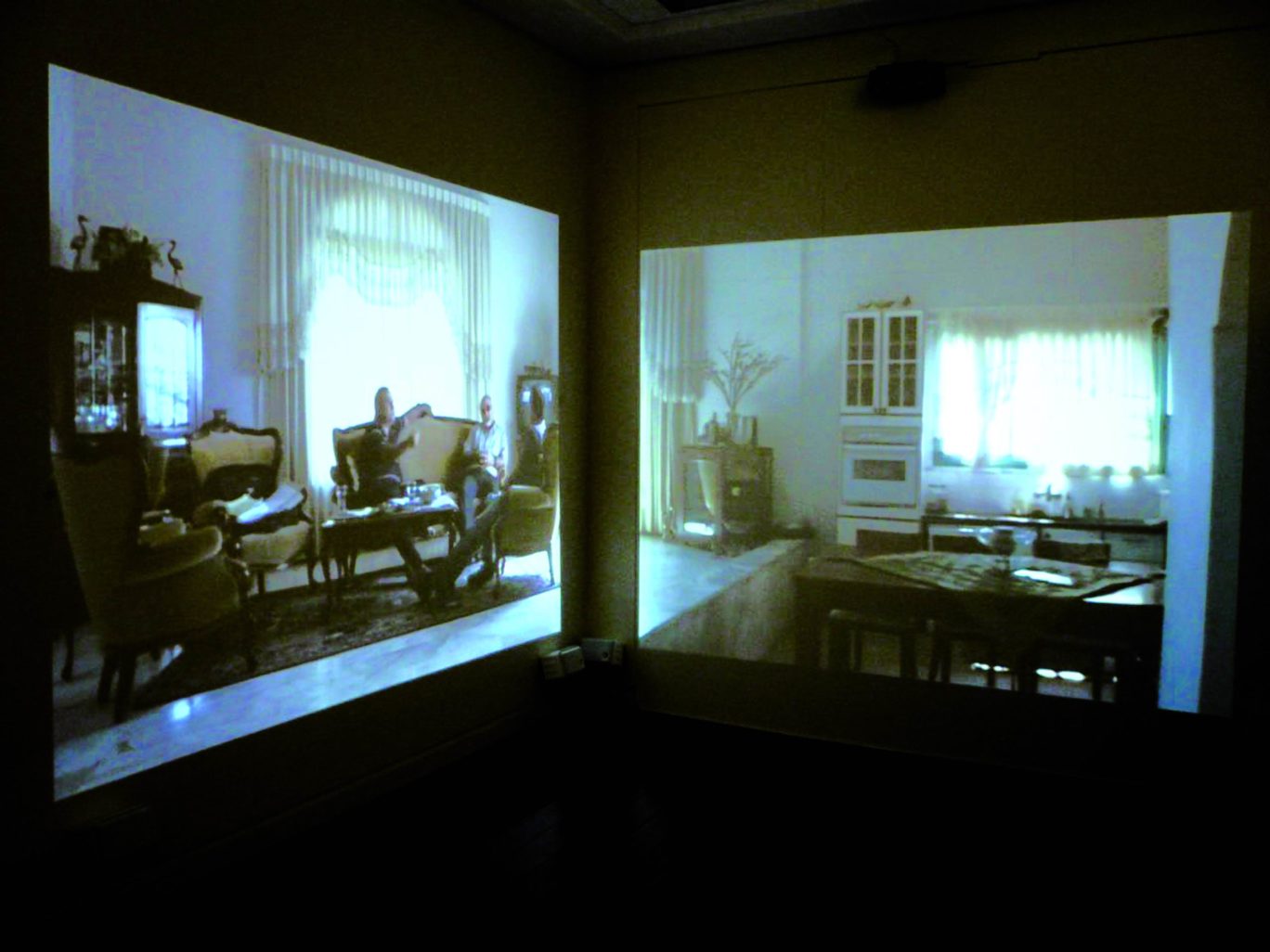

The installation reconstructs an ordinary routine in the Chacar residence in Jaffa on a Saturday. Bukhari and Danon installed four video cameras in the apartment which documented the ongoings over several consecutive hours. The static cameras document a conversation in the living room between the owner of the house, civil engineer Nahle Chacar, his friend Ghaby Aabed, the Chairman of Al-Rabbita, and Sami Bukhari. The three talk about politics and about life, while the activities of the rest of the family members and their visitors in the kitchen and living room are given equal attention. The result is projected on four screens concurrently, so that when the figures move from room to room, they disappear from one screen and reappear on another.

The location of the screens and the size of the images projected on them are faithful to the proportions of the apartment plan and the size of its rooms, so that the ostensibly-neutral gallery transforms, for the duration of the show, into the interior of the house in Jaffa. The occurrences in the apartment take place by themselves, unaffected by the viewer. Furthermore, the conversations are mostly held in Arabic, and may only be comprehended by the Jewish audience through the accompanying translation distributed at the show. The absence of immediate translation elicits the thought that the sense of security granted to Palestinians in Israel by their house is due to the ability to speak Arabic freely within it, and that the choice to use the spoken language—which is the minority language—in the installation, outside the domestic context, undermines the power relations between Jews and Palestinians in Israel.

The exhibition endeavors to tie between a discussion of Palestinian architecture and the discourse of identity. Bukhari and Danon avoid stereotypical representation of architecture in Jaffa. The residential apartment presented in the installation is part of a contemporary building reconstructed more than a decade ago on the ruins of a Palestinian house. Populated by members of one extended family, the three-storey building does not comply with the pre-1948 Jaffaesque building style. The apartment plans are not traditional. The façade combines traditional Jaffa building details with contemporary modern design.

Excluding the choice of site in which the installation takes place, the exhibition “A House in Jaffa” prefers to recount the social story of Arab architecture over engagement with the architectural structure, thus criticizing the disregard typifying the architectural discourse with respect to Arab architecture in its socio-political context and its concentration on aesthetic and stylistic issues. To wit: it argues that while Palestinian society has been pushed to the margins, Arab architecture, as detached from it, has gained a special status in Israeli architecture, and that its dissociation from the context of the power relations in Israel has positioned it as an alternative, even as a source of inspiration, for modern architecture. Thus it may be appropriated in order to establish cultural domination of the space.(2)

The story revealed in the exhibition involves the authorities’ policy regarding residence of Palestinians in Jaffa. In the late 1980s an urban renewal project replaced the policy of the Tel Aviv Municipality which was characterized by neglect, a building freeze , planned demolitions, and residents’ evacuation from Jaffa.(3) Processes of urban renewal have improved Jaffa’s physical condition in comparison to other mixed cities, and the dizzying increase in property value in the following decades has led to an influx of well-to-do Jews into the heart of Jaffa’s deteriorated Palestinian slums in a process of gentrification—luxury construction which pushed out Palestinian non-property owners from the area.

Founded in 1979 by educated free professionals, Al-Rabbita operated within this political reality, striving to improve the situation of the Arab minority in Jaffa both by activities within the population and by turning to the establishment. It represents Jaffa’s heterogeneous Arab population, with all its religious groupings and social strata. The organization holds activities pertaining to issues of urban planning, mainly as they relate to housing solutions for the Arabs of Jaffa. The recognition that the process of gentrification brings about further Judaization of Jaffa, this time via market forces, has given rise to disappointment among organization members and fears of the urban planning. (4) These fears were confirmed with the eviction orders issued in 2007 by Amidar (5) to 497 Arab families in the al-Ajami neighborhood whose rights to the properties were not settled.

The conversation documented in the installation links the architectural scale to urban and political concerns pertaining to Jaffa. It focuses on the reduced accessibility of Palestinian citizens in Jaffa to housing, addressing the issue of housing in Jaffa as an expression of a multiplicity of identities and of social, political, and class gaps between populations in Tel Aviv.

1. The exhibition was part of the project “Autobiography of a City,” www.jaffaproject.org.

2. E.g.: a pioneering study by the Jaffa Team in the Engineering Department of Tel Aviv Municipality carried out in the late 1980s, “Perusing al-Ajami: An Architectural Portrait” [Hebrew].

3. Gila Menahem, Shimon Spiro, Politics, Bureaucracy, and Letting Residents Participate in the Urban Renewal Project: The al-Ajami Case (The Pinhas Sapir Center for Development, Tel Aviv University, 1992) [Hebrew].

4. From an interview with Nahle Chacar, September 2003.

5. In 1948, Amidar (Israel’s National Housing Corporation) and Halamish (government-municipal company for housing renewal) were given all the properties in Jaffa declared absentee properties by the Administrator General and the Israel Land Administration. The Palestinians became statutory tenant.