Eran Binderman forsakes the great effort required to preserve the rare, vulnerable nature within the concrete forest. With the freedom of an architect, a child of the image era, he replaces natural vegetation with an industrialized, mechanized representation.(1)

“Foodscapes” addresses the discussion concerning the distinction between nature and culture in international architecture. (2) “Foodscapes” are not nature. They are mechanized and artificial, undermining this very distinction: while simulating agriculture, they are made of consumer goods from the food industry.

The industrialization of agriculture has led, inter alia, to changing the nature of agriculture and the global food market, reducing the number of those working in it, and to abandoning agricultural land. Western farmers require government support to survive. In Israel, due to the scarcity of land, former agricultural land is in high demand as land reserves for future construction. Thus the image of artificial agriculture in “Foodscapes” introduces a perception whereby not only the natural but also the agricultural and processed is worthy of preservation.

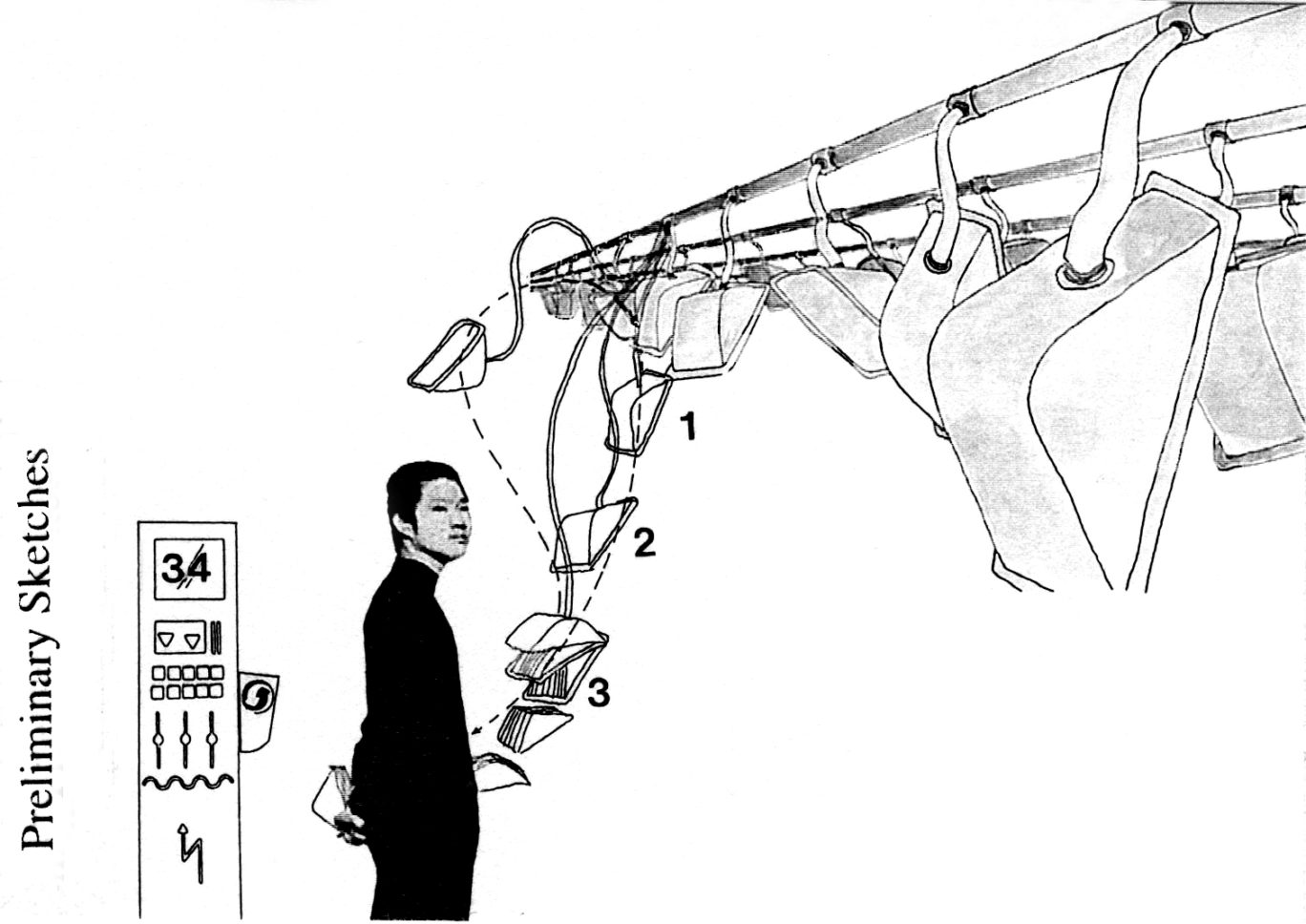

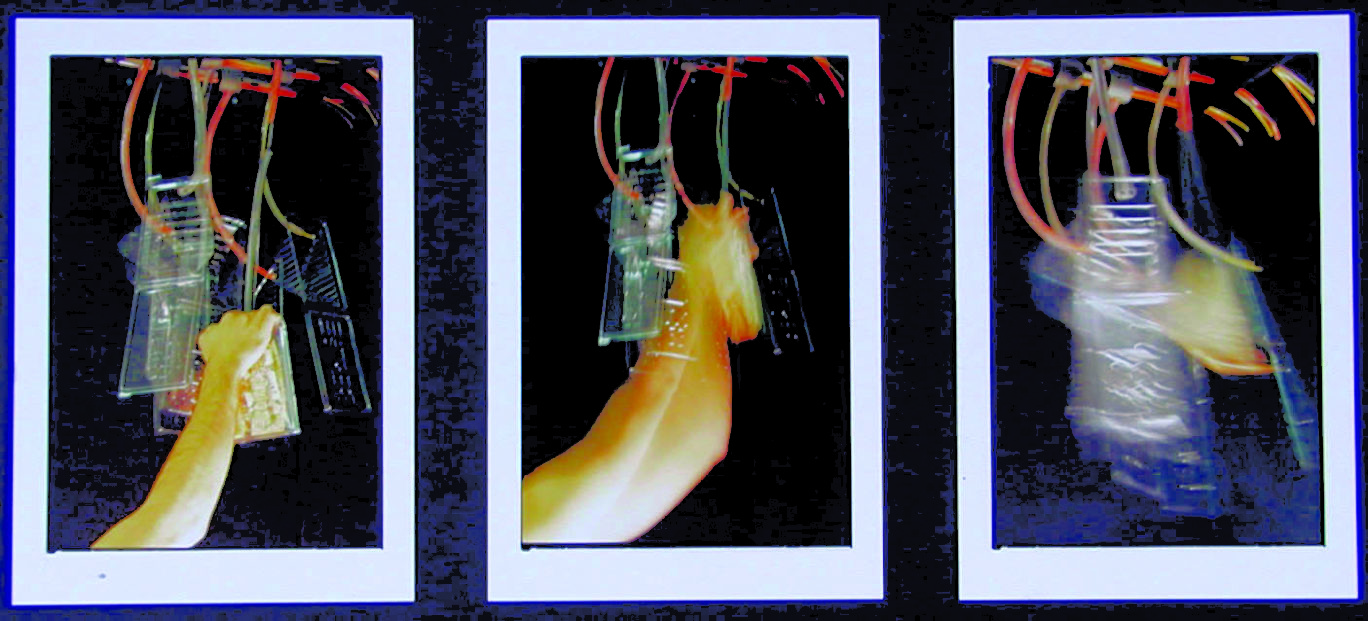

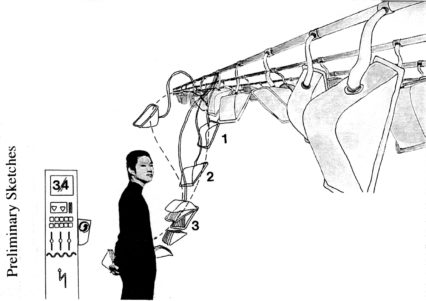

In the act of picking prepared food, the bodies of the passerby in the city square and the visitor to the exhibition reinstate an inkling of the lost relationship between man and the fruit tree. Instead of the tree, however, a mechanized pergola towers, and instead of the natural fruits to be picked—sandwiches wrapped in transparent triangular plastic packs; the mechanized process of the food’s distribution, refrigerating, and selling is reinforced by the highly-nuanced design of the architectural machine. All these remind the user, as he stretches his hand to pick a sandwich, how far we have come from nature, and how industrialized our agriculture and food production have become.

The automatic grove thus brings together, unnaturally, the perfect life cycle of nature with the food industry’s production line. The automated orchard sells vacuum packed fast food, thus eliminating the part of the food industry workers. In contrast, the exhibition exposes the commercial role of the municipal park. Not only are these scraps of urban nature explicitly designed, built-up and unnatural, they are also consumed like any commodity of the leisure industry: public parks in an urban setting are intended, among other things, to draw population to the city and to promote economic turnover; public parks in new neighborhoods are built by the entrepreneurs for sales promotion, and entry into some of these parks and the participation in activities held in them often involves payment of a fee.

Following contemporary and postmodern architects such as Venturi and Koolhaas, who explore the interrelations of modern architecture with commerce and the media, transforming architecture into a surface for advertising, “Foodscapes” acknowledges the power of commerce, eating, and their combination for the revival of run-down urban public spaces. It even employs market forces to transform the eating experience into a social experience in the public sphere. Binderman does not reject consumerist culture, nor does he try to clean the public sphere of market forces, as proposed by cultural critics. On the contrary: he proposes to fuse the park itself with consumption in the city square, at the heart of a public space which is not commercial, believing that if commodity cannot be avoided, the brand must be exploited for the benefit of designing the urban setting.

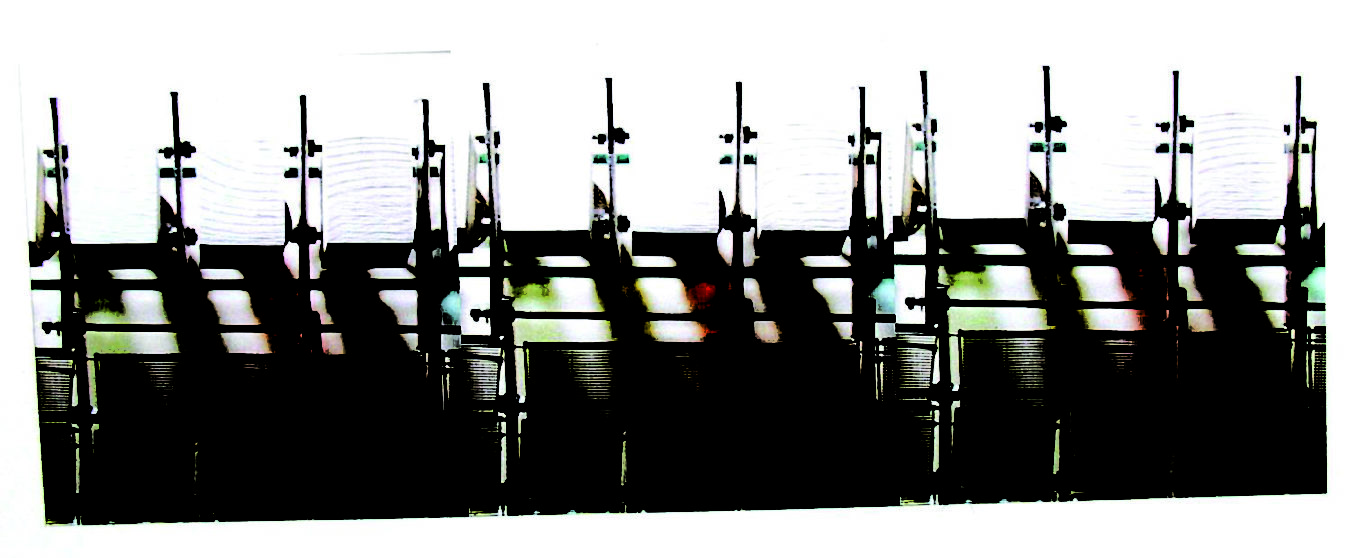

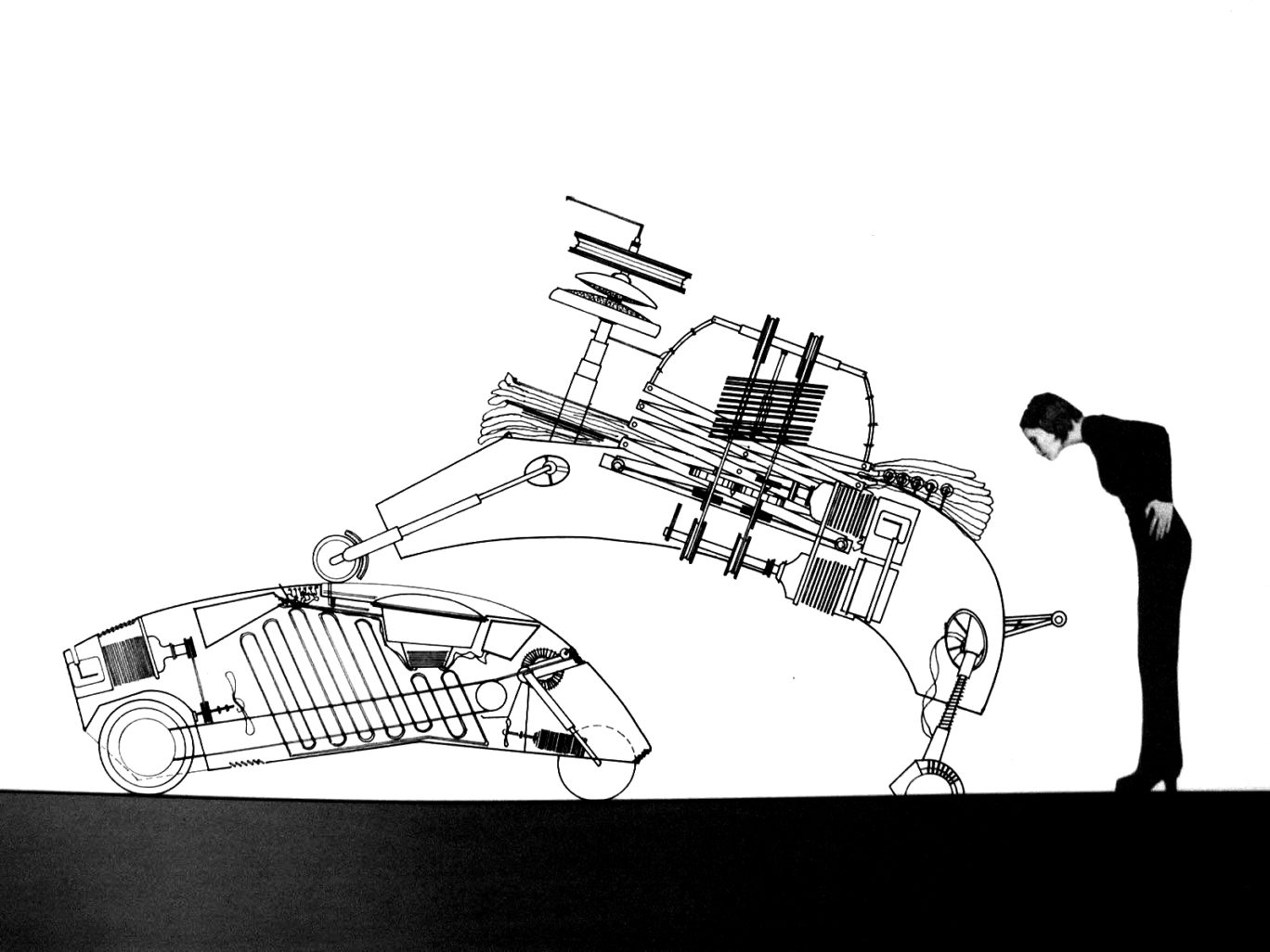

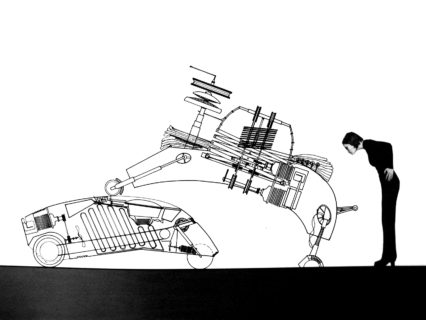

Binderman invests planning effort in the mechanization of the food sale phase, which is the shelf/counter phase in the food and fast food chains. This phase is usually practical. The transportation means involved in it are basic, and the work force is young, unskilled, and cheap. Since mechanization is not necessarily efficient or economic, Binderman’s proposal for mechanizing the food sale in “Foodscapes” is not only a carefully planned practical elaboration, but also an expression of the thrill with the machine. In this he joins a modern tradition which turns to the machine as a source of inspiration, and specifically the fantastical technological vision of the British Archigram group active in the 1960s and 1970s.(3)

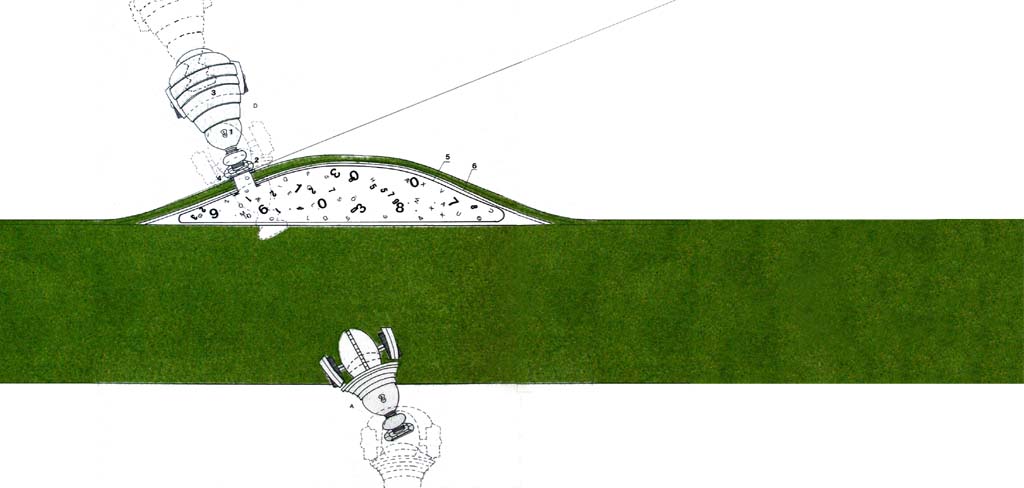

The figurative, plastic design language of the machines in “Foodscapes” is, thus, consciously anachronistic. In the mechanized food park, the “waste disposers” invented by Binderman are machines which resemble living creatures. They are user-friendly, compressing the waste of fast food packaging under Astroturf lawns, thus lending the surface the appearance of “artificial topography.” To wit: the ground at the foot of the food park is dynamic, changing according to the cycle of meals.

In “Foodscapes” Binderman offers an alternative for non-resilient architecture based on preplanning of a final product and a prolonged process of realization at the end of which the building might well lose its relevance to changing needs. The architecture of the current project, on the other hand, is changing and flexible. Binderman sought what he termed “generative architecture” in his text for the exhibition; architecture created and changed by its users, enabling intense human occurrence with maximum flexibility. His architecture generates a set of human occurrences, which infuse ordinary urban spaces with a dynamic quality by means of movement, needs, and the routine actions of passersby.

The consumer goods in the exhibition space form an architectural sensual celebration, partly realizing the architectural machines designed by Binderman; meant to be eaten (on opening night the audience was invited to taste them), they form a live simulation of the way in which “Foodscapes” generate a dynamic occurrence in space.

1. The design of “Foodscapes” was developed as part of Eran Binderman’s M.Arch. thesis at the Bartlett School of Architecture, London.

2. For an elaborate discussion of the notion of “artificial landscape” see: H. Ibeling (ed.), The Artificial Landscape (Rotterdam: Nai Publishers, 2000).

3. Archigram’s influence may be identified in “Foodscapes” both in contents addressing consumer culture, and in the spirit of optimism, unpractical nature, and the yearning for flexibility. Peter Cook, one of the group’s leaders, is the Chair of the Bartlett School of Architecture, London, and one of Binderman’s advisors in this project.