Reproduction of Educational Buildings in Israel

“Eshkolot Payis” are culture, art, and science centers built by Israel National Lottery to provide clusters of infrastructures and services to schools. Almost seventy such edifices, fully replicated, have thus far been erected in various sites and settings throughout the country. With the aid of Israel National Lottery other educational facilities have also been designed and built: sports hall, roofing for basketball courts, “Tapuhim” (-“apples”; smaller cultural centers) and “Kotarei Payis” (libraries). These educational facilities, which are usually strategically located on the main road or on a hilltop, take part in shaping the public sphere in Israel.

Replicated or reproduced architecture of schools and education-related buildings in Israel takes place in the span between construction of an architectural type repeated with small variations, based on programs conceived by the Ministry of Education, and full replication of buildings, at times industrialized. The quintessential Israeli school types evolved during the country’s first decades, when need was great. During that time the programs introduced by the Ministries of Housing and Education for schools were also established. These determined the size of classrooms and corridors, and were preserved over the years with minor variations.(1)

The architectural type is based on correlation between a built form and its use; it is underlain by an architectural principle shared by many buildings. In the history of architecture there are known building types that have gained symbolical value. In the Israeli context of the school system, the type has been trivialized. Schools, mainly primary schools, scores of which were constructed throughout the country, were named after the contracting companies that built them for the local authorities and the Ministry of Construction and Housing. The semantic transition from an architectural type to a builder’s type, and from implementation of a fundamental scheme to reproduction of an entire building (at times with slight variations) reveals the influence of the planning and implementation procedures, and of the politics of governmental and municipal planning on the design of public buildings in general, and educational facilities in particular, in Israel.

The exhibition “School Uniform” presents two different modes of reproduction—one is standard, formally nondescript reproduction discernible in the industrialized schools constructed in the planning and implementation method, photographed by Orit Siman-Tov; the other is the reproduction of the unusual characterizing the “Eshkolot Payis” and other spectacular educational buildings photographed by Eyal Danon. While the reproduction of the standard arouses antagonism due to the interruption of architectural uniqueness, the reproduction of the exceptional raises antagonism due to the dissemination of ephemeral architectural trends foreign to the act of reproduction.

Orit Siman-Tov photographs several types of schools and kindergartens built throughout Israel based on imported (industrialized) prefabricated construction methods from the late 1960s to the 1980s. While the schools are indeed photographed from the outside, through Siman-Tov’s eyes the schoolyard transforms from exterior to interior—into a place which is somewhat somber, yet remains etched in many childhood memories: a modest space devoid of walls, whether paved or not, delimited by the school building, the path and the fence, touched by human signs, among them basketball backboards and sandboxes (see pp. 37, 40).

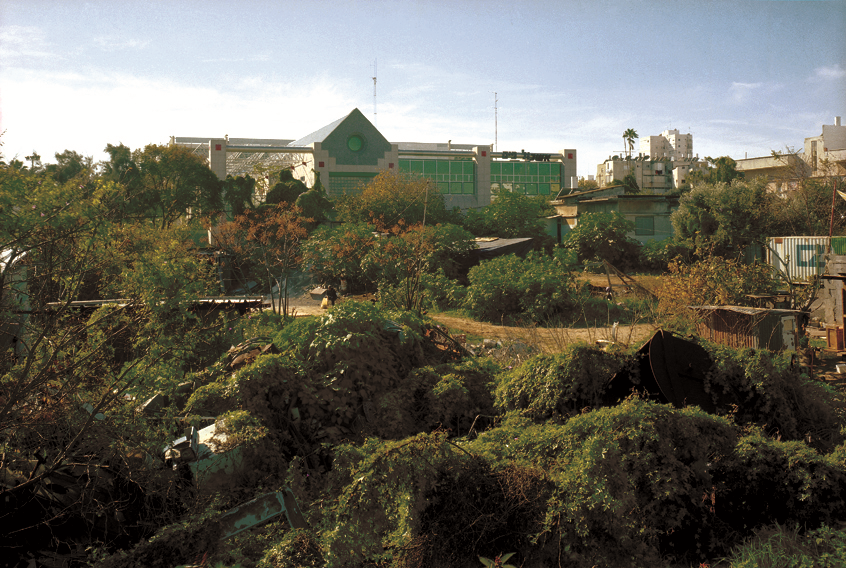

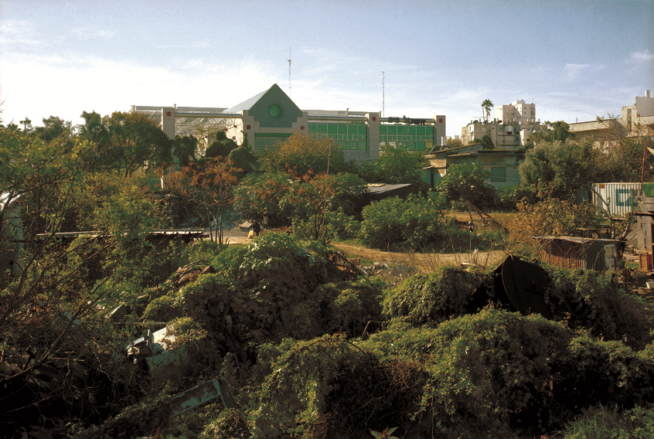

Eyal Danon presents a series of photographs depicting “Eshkolot Payis” in various places in Israel (see pp. 38-39). In Karmiel he documents an “Eshkol Payis” in all its grandeur in a frontal photograph. In other photographs Danon relies on the viewer’s acquaintance with the familiar building, and invites us, as if it were an identification game, to pinpoint it within the context. Danon observes the environmental context of the building. He expands the photographic gaze beyond the individual frame, photographing yet another peak at the typical setting of the “Eshkol.” The Israeli identification marks in the landscape thus become the major theme of the series (see cover image).

Planning and Implementation of Public Buildings

The conventional construction method of public buildings sets apart the planning and the implementation. Once the planning phase is concluded, a tender is held, and the contractor who submits the lowest bid is selected to implement the job. This method guarantees planning, implementation, and high-quality materials, yet demands long planning, and is not economical budget-wise.(2)

In contrast, the standard schools addressed by “School Uniform” are constructed according to a method whereby both planning and implementation are contested in a tender. While the tender indeed includes the planning aspect, the chosen contractor is nevertheless selected based on the lowest bid, and therefore economic considerations during the planning process precede architectural and pedagogical considerations. “Planning and implementation” types of buildings obey a basic program dictated by the Ministry of Education and Culture, without adapting it to the unique characteristics of the specific school being planned, its location, and the pedagogical method to be implemented in it. Furthermore, they are not suitable for the addition of classrooms or for construction in phases, as required in many schools.

In defense of standard educational building architecture one may say that it has provided an adequate, uniform level of school facilities. The reproduced and industrialized schools were usually planned satisfactorily and at a reasonable cost, within a short span, displaying a good level of execution. When the Ministry of Education was preparing to upgrade old schools, these were still in good repair; it turned out that their physical conditions were better than those built using conventional construction methods. On the other hand, they rated poorly in terms of the quality of planning and functionality.3

The standardization of construction enabled supply of many suitable classrooms in a period of grave shortage. Full reproduction of educational buildings, however, raises many questions being antithetical to architectural values: modernist values which emphasize architectural innovation, originality, and creativity, and postmodern values, which take into consideration the environmental context of the building, its significance, and the identity of its users.

Financing, Planning, and Construction of Educational Institutions

During the 1950s and 1960s educational facilities were built mainly by the Ministry of Construction and Housing as part of the construction of new settlements and neighborhoods. Towards the late 1970s the central government’s authorities were decentralized, and the budgets and building authorizations of educational institutions were transferred to the local authorities and the Local Authority Administration. From the late 1980s the Ministry of Construction and Housing virtually stopped building schools altogether. Non-governmental organizations owned by the local authority—initially LGEC (the Local Government Economic Services of the Local Authority Ltd.), and subsequently Israel National Lottery—joined in the construction of educational institutions, helping the local authorities in the complex task of school construction. In the transition from centralization to decentralization, the central government wanted to increase the share of the local authorities in financing the services and development via independent sources.(4)

Israel National Lottery started supporting education some fifty years ago, helping in the construction of numerous educational buildings. During the 1980s the Lottery transformed from a financing institution to an organization which not only provides funds, but also initiates and implements construction of educational facilities in Israel. Since 2002 Israel National Lottery has also been a major player in the construction of schools (“classrooms”). The confirmation of needs, the programs and the plans for these schools are all performed by the Ministry of Education.(5)

The unification of the architecture of educational buildings in Israel is not a necessity. Within the Israeli educational system itself a policy has evolved since the late 1970s encouraging diversity and pluralism, calling upon local authorities (not necessarily the strongest among them) to innovate in the design of schools, and to adapt the schools to teaching methods which focus on the student. The Lottery’s choice to replicate educational buildings, in contrast to the current policy of the Ministry of Education, stems from an economic logic striving to exploit the centralized advantages of a single company catering to many authorities.(6) It is a centralist modus operandi which replaces the centralist work mode of public planning customary in the first decades of the state.

Replication of educational buildings was intended to provide services to the public, but it also has a representative dimension. A citizen of the country, traveling along its roads, experiences the recurring buildings as representing the state’s power institutions. The architecture of the reproduced buildings usually represents a professional and social hegemony which is fairly homogenous in terms of architectural taste, class, and social origin. Its dissemination by means of reproduction interferes with the way in which the space represents disempowered sectors in Israeli society, mainly because the reproduced educational edifices were being built mainly in localities limited in their financing and planning resources, many of them Arab and Bedouin.

1. Reut Gordon, “Consciousness Builds School Builds Consciousness, a History of School Buildings in Israel: Education, Society, and Architecture,” MA dissertation, Faculty of Humanities, Tel Aviv University, 2003.

2. Architects who design educational buildings maintain that it is still possible to provide unique architecture within the Education Ministry budget, which is tailored to the school’s site, content, and community. See: “Seminar: Quality and Diversity in Educational Facilities within Budget, Position Paper,” Perspective: Architectural Review, 12 (Feb. 2002): 30 [Hebrew].

3. U. Harmel (ed.), Study about Planning and Construction Procedures of Primary Schools in Israel (Tel Aviv: Institute for Development of Educational and Welfare Facilities, 1991) [Hebrew].

4. Nahum Ben-Elia and Shai Cnaani, “Costless” Local Autonomy: The Issue of Educational Facilities Funding (Jerusalem: The Floersheimer Institute for Policy Studies, 1996) [Hebrew].

5. From a telephone interview with Mr. Simcha Schneur, Deputy Director General, the Ministry of Education and Director of the Administration for the Development of the Educational System, December 2003.

6. From the website of the Local Government Economic Services, http://www.mashcal.co.il/english/home.htm.