From objections to planning: Three moments of alternative planning

The resident’s involvement in urban design is not, at present, an integral part of the process. His only window for participation is when it comes to submitting his or her objections to a proposed planning. Urban planning is a long and complex process where many professionals collaborate. They have the power to change, promote and approve plans. The public, on the other hand, is only invited to submit its objections after the plan is completed – this, in order to minimize any chance of it actually modifying the completed plan. In fact, the 2012 planning annual shows that only 3% of total unapproved plans were rejected due to public objections. It is clearly evident that the resident’s power to affect the planning procedure is frightfully small. The resident is barred, de facto, from participating in the processes that shape his or her life.

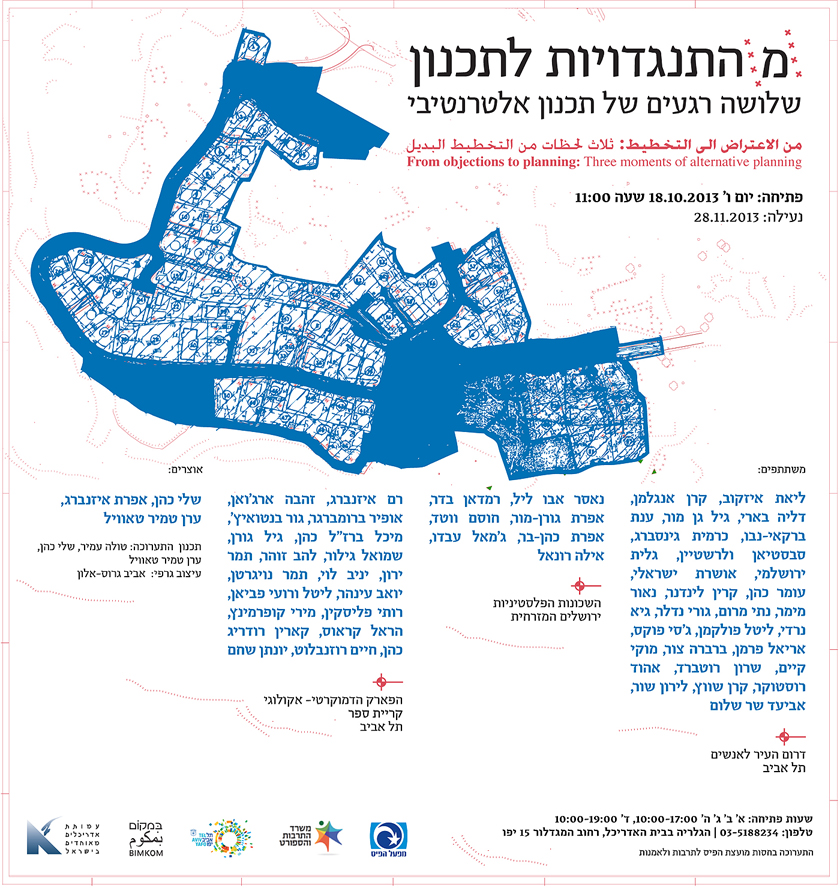

The exhibition shows cases where a group of residents, professionals and civil society organizations managed to propel planning processes that expounded their own vision of urban space, a fundamentally different one from that intended by the authorities or propelled by the market. In the following three cases, groups of residents initiated their own alternative planning in an attempt to alter or even cancel an existing plan. In these sites it was the combination of the spatial needs with the human capital of the group that achieved the desired bottom-up change. The exhibition shows the beginning of residential organizing through its different stages, up to the alternative planning produced. First, a district outline plan (confirmed last year) regulates the existing structures in a neighborhood in eastern Jerusalem, and adds future construction options. Second, a public park replaces an intended luxury condominium. Third, an alternative planning initiation for southern Tel-Aviv neighborhoods challenged and even somewhat altered the city’s outline plan. The activists wished to gain access to where planning decisions are made. They demanded that the authorities listen to the residents, consider their suggestions, and provide adequate solutions and assistance.

The Kiryat Sefer park was opened in 2013 in central Tel-Aviv, an area generally lacking in open spaces. It is emblematic to the ability of a determined and well-connected group of residents to alter local planning, and turn a would-be luxury condominium to a public park. The residents identified a half-empty plot as their last chance for a green communal space, and followed different strategies to change the plot’s designation. They organized protests and conventions, and managed to preserve an existing structure as a legacy site. In the following years, they visited the preserved gravel plot as a would-be park. Their tenacious, multifaceted and active struggle ended in victory when the municipal authorities accepted their demands, reversed their previous planning decision, and opted to support the public interest by building the park. The organizational platform continued to closely accompany the park’s planning to see the project to completion.

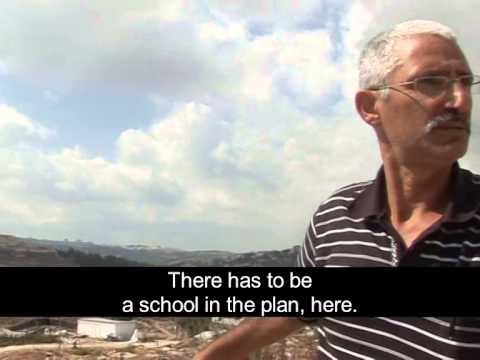

Unlike the Kiryat Sefer park, the organizing residents of eastern Jerusalem are a marginalized group: the initiative for 2012’s plan no. 9713 for the Al-ashqariyah area, in the Beit-Hanina neighborhood in northern Jerusalem, was the work of one man. Following the partial demolition of his home, he decided take action. He organized his neighbors whose homes were also in danger of demolition, and together they appealed to the neighborhood committee to assist them with selecting their own architect and pursuing the planning procedure to its completion. The move ended with a plan that regulates existing structures and allows for future construction. The eastern Jerusalem planning initiative therefore revolved around the housing shortage, the crumbling infrastructure, and the dire lack of public spaces in Palestinian neighborhoods. These flaws are the result of continued planning failures and omissions by the authorities, guided by a long municipal and government policy to strengthen Israeli control of occupied territories. Nonetheless, change can be seen in the authorities’ willingness to openly listen to residential planning initiatives. Architect Efrat Cohen-Bar of the Bimkom organization, together with architect Ayala Ronel, analyze this and similar initiatives, and suggest detailed ways to propel and realize them by what they term “actionable plans.”

Most alternative planning initiatives are rooted in active residents who focus mostly on their immediate surroundings. By contrast, the “Drom TLV” project came up with a plan that challenges most of the existing statutory municipal planning, spanning more than half of Tel-Aviv. This alternative planning seeks to protest against the neglect of Tel-Aviv’s southern parts, a state of affairs that has hardly changed since the city’s founding. It is true that here, too, the active group was equipped with resources usually unavailable to most. It even won support from the Society for the Preservation of Nature in Israel (SPNI) – one of Israel’s most prominent NGO’s in alternative planning. But the residents’ voluntary organization does pose fundamental questions about the way urban planning is now done. In a series of presentations given to various resident groups and shared online, the team presented their detailed analysis of the inequality of planning between city’s northern and southern parts. It provided a broad historical background of the city, and laid down alternative planning principles for a new urban outline plan. It produced a new zoning plan that challenged the ideas at the base of the current one. Their comments were acknowledged by the authorities, yet their influence on the yet-unapproved outline plan remains to be seen.

Since the 1960’s, central modernist design has weathered many challenges. Davidoff, Alinsky and Arnstein are commonly mentioned as propagators of alternative planning discourses and practices. This they did through their work on advocacy planning, their collaborative, including planning, and their manifests calling residents take control of their space. Their work has led to further developments such as radical planning, egalitarian planning, collaborative planning, communicative planning and more. These different approaches have had an effect on planning thought and rhetoric, and pose fundamental ethical questions such as: how can one talk about planning? To whom? What are good planning products? what does just planning look like? Still, more than half a century after these debates were sparked, most urban planning is still done behind closed doors. Furthermore, it seems urban planning is increasingly driven by semi-hidden political and economic interests.

And yet, despite existing centralized planning procedures and trends, urban residents are working to mitigate and stop the increasing commodification of their living space, and work to find planning alternatives that would enrich the quality of their daily lives. The mass 2011 worldwide protests, which took place in about 1000 cities in over 80 countries, also argued for “the right for urbanity”, which includes the right to resist, influence, decide, and (consequently) to plan. The protests brought to light many public initiatives and efforts, unseen or unnoticed before.

One might ask if and how, bottom-up planning actions like the ones discussed here manage to affect the municipal planning processes. Of special interest are the actions perceived as successful: do they change the ways of the establishment, mitigate it and open its doors? Or does the current establishment simply pay lip-service (when convenient) in order to pursue its interests through other channels? What are the formal planning mechanisms required to enable, facilitate and support residents’ planning actions? And what are the advantages of bottom-up planning absent from central planning?

As for the three bottom-up actions described above, one might ask: what are the more efficient ways of bottom-up planning? Do marginalized group need strategies different from those used by hegemonic groups? What abilities and strengths do residents, whoever they might be, have when it comes to planning? And what can Tel-Aviv planners and architects learn from east-Jerusalem actions like the one described here?

The initiatives described here reveal a complex reality. It is viewed differently by different groups of residents, depending on their proximity to hegemonic planning, the scale and magnitude of their alternative plans, and the extent to which they clash with the establishment’s interests. The initiatives expose the wider economic and political context of planning actions: in eastern Jerusalem, each success must be measured against countless failures, whereas in Tel-Aviv, favorable press coverage aids some actions succeed, but might not be enough to change the corporate or establishment’s approach to urban development. Despite these differences, the exhibition sheds light on the similarities connecting these three moments when alternative planning prevailed, and highlights the creativity of the residents who began and persisted in their struggles. The exhibition also presents the key figures in the struggles: residents who took the leadership, unbiased mediators, and architecture professionals who shared their knowledge while listening, truly listening, to these communities.

* The author thanks Tula Amir, Efrat Cohen-Bar and Ayala Ronel and Sharon Rotbard for their contributions.