Soon after Israel was founded, in 1948, many housing projects were hastily built to accommodate tens of thousands of new immigrants. The project apartment’s internal planning was based on architect Alexander Klein’s analytical developments. An Odessa-born Jew, Klein worked in the housing projects around Berlin from 1920 through 1933, when the Nazis rose to power. Klein saw the apartment as a machine for living: efficient and smart. He studied the inhabitants’ daily lives in the apartment, its spaces, the light entering it, and the shades cast by its furniture. In light of his findings, he developed a whole new residential apartment, divided to two parts: a public part, shared by all family members and used to entertain guests, and a private part that includes several bedrooms. In other words, he separated the kitchen, the dining hall and living room from the baths and bedrooms. These principles, so trivial today, were only formed in the early 20th century.

The Israel’s housing projects were built in light of Klein’s new perception of living. But unlike earlier Israeli residents, the population for whom the projects were meant did not necessary share the same living culture. A symbiotic combination of internal and external spaces, so typical of warm climates, was critically absent from the projects designed in cold, far-off Germany. Multi-purpose, multi-territorial spaces in which the family could sleep and spend time together were never planned, as these concepts were alien to Germany’s individualistic culture. This was the start of an internal, structural conflict between the planners’ living culture and that of a major portion of the tenants. This conflict became evident in the way the tenants used their apartments – differently from the planners’ original intentions – as well as in their alternative, clearly non-modernist internal design.

_________

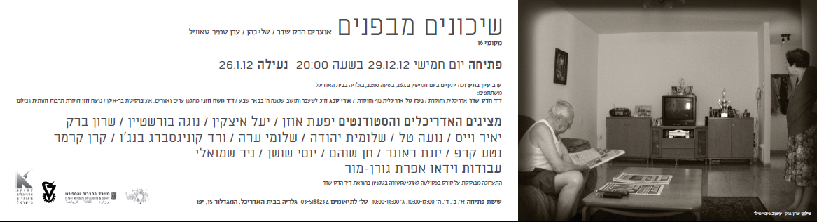

Today, sixty years after Israel was founded, when the cry for public housing evokes a longing to a time when the state, through its public housing projects, took responsibility to meet its residents’ housing needs. Now might therefore be an appropriate time to examine not just “the great act” of Israel’s founding, but also the millions of smaller great acts of the seldom-mentioned tenants. As an immigrant country, Israel is a fascinating example of an encounter of two different living cultures that had clear architectural results. Through indoor and outdoor pictures of the projects, conversations with their tenants, and a sensitive and informed view, the exhibits explores the many ways in which living culture clashed with – and sometimes complemented – the architecture.

Behind the repetitive, undistinctive fronts of the generic housing projects, one might find here alternative aesthetical and cultural expressions of “the home” – a home modified to fit its tenants, like an old shoe shaped by the foot that occupies it. A home which, due to the sense of permanency bestowed by its walls, created the necessary infrastructure from which the tenants could embark on their own individual journeys. A home which, despite its stature and indistinctiveness – was loved by its tenants.

________

1. They’ve been living in Netanya’s Dora housing project since 1957. Before that, they lived in Iraq, where they enjoyed a large, three-story house, with six rooms, two indoor bathrooms, and an uncovered rooftop terrace. Curiously, the house had bedrooms, but no common living or family room. Instead, an internal yard with a water-well was used as the shared familial space, where friends and guests visited from time to time. In Israel, the project’s front yard was used as the family living room. At its side, along the fence separating their yard from their neighbors’, were a bed and some folding chairs. In hot summertime, the dining table was moved from the hall to the yard, to free some indoor space. The hall could then be used as a bedroom. It contained a bed, a refrigerator, a table and several chairs. The family had their meals there, with some family members sitting on the bed, others at the chairs opposing it. At night, the bed was occupied by the great-grandmother, and later by the son on his periodic returns from his IDF base.

2. She’s been living in Givat Olga for 39 years. Born in 1940, she is a widow and the mother of nine children. Some time before, in Morocco, she had an apartment in a luxurious condominium, but in Israel received only two project apartments. Despite some pleas, the two apartments were never joined together. “We got two apartments,” she says, “we put two kids in each room, and my husband refused to tear down the wall separating the two apartments, so that we would always have one home neat and organized, without the kids’ mess.” They lived their daily lives in “the messy house.” The “neat house” was used only when guests came to visit.

These two stories are part of the “Inside Housing Projects” exhibit. They reveal an often-neglected aspect of public housing projects – the story of their inhabitants. Their different cultures of origins, so different in their housing and living patterns, are in clear contrast to the project apartments and the planning ideas behind them.

What might we conclude from the two examples mentioned here? Was it possible to have done otherwise? Is there a lesson to be learned here, relevant for the here and now?

The exhibit’s “Inside Housing Projects” expose the gap between the living cultures of the planners and the tenants. The obvious quantitative gap is evident in the small spaces of the apartments compared to the large families they inhabited. When eight family members must live in a one-bedroom apartment, multi-purpose furniture and spaces (used as both common rooms as well as private studies and bedrooms) become not only desired by inevitable. It must be noted, however, that it is a view in retrospect to suggest that larger apartments should have been built for the tenants. This was probably not feasible in Israel’s first years, when the Jewish population doubled within three years, and tripled by the end of the first decade.

And yet today’s view reveals that the tenants could indeed have benefited had the apartments’ public spaces been originally designed as one larger space. Had the hall, the dining and the living hall been planned as one large space, the tenants would have been given a sense of space. Furthermore, it would have enabled a multi-purpose pattern of living so characteristic of many tenants’ culture.

Today, as global media continually blurs cultural distinctions and housing preferences, it seems as if everyone has the same dream – a single-family house with a back yard, or alternatively – a luxurious penthouse at the top of a fashionable condominium. A specific style of design – open and white – is dominant in most commercials and magazines. One might plausibly conclude that one design is appropriate for everyone. That would surely be a mistake.

Israel’s mass protests of 2011 shed a new light on the gap between the existing housing supply and a general longing for a sense of togetherness. Indeed, most tenants expressed a desire for urbanity and intimacy, and a practical need for small apartments that feel connected to the urban experience. The exhibit shows that more open-minded planning could allow the smaller apartments to accommodate many different scenarios, and to be adapted more easily to inevitable life changes or cultural differences. The exhibit also implies that the external environment is just as important as the actual apartment: a yard can be viewed as an extension of the house, and “home” includes sometimes the adjacent street, the walkway through the public park, and the daily route to the grocery store. Finally, the exhibit reminds us that planners must always be attentive to the needs and wishes, both physical and cultural, explicit and implicit, of the tenants they serve.