Relli De Vries is an artist and landscape architect. Her exhibition, “Moving Israel’s Coastal Highway,” zooms in where the Coastal Highway (also called Route 2) meets Jisr az-Zarqa, an Arab-Muslim town. The part of the road that borders the town to the east has been so planned as to approach the town in a curve, and was paved over lands expropriated in 1967-1970. According to Netivei Israel (Israel’s National Transport Infrastructure Company Ltd.) and the town’s engineer, the current path takes advantage of the underlying kurkar rock (Hebrew/ Arabic for aeolianite). This was supposedly preferable to paving the road over the unstable swamplands to the east. At the same time, however, the road does expand eastwards later on, paved on specially-built infrastructure.

Relli De Vries therefore examines Route 2 in a broader political context, identifying it as a social and environmental hazard. The road is physically close to the town, it is true, but it also prevents the social and economic development of Israel’s most densely populated town. Jisr’s main access point is through Route 4, via a narrow unpaved road that travels beneath the elevated Route 2. Public transportation access is therefore severely limited. In addition, the townspeople’s attempts to cross the busy Route 2 have cost many lives. The road effectively traps the poverty-stricken town in an enclave between two Jewish settlements: to the south, wealthy Caesarea has built a dirt levee (which gained much attention); to the north, Jisr is bordered by the Nahal Taninim nature reserve, itself bordered by the Ma’agan Michael kibbutz. De Vries thus reads Route 2 as spatial discrimination against Jisr’s Arab residents, planned and executed by the state. Today, Jisr ranks very low on Israel’s socio-economic scale.

The idea to “move the coastal highway” might sound like a radical, even provocative suggestion, but it is in fact a very viable option frequently discussed when new planning options are discussed for Jisr. Existing comprehensive plans include both the upgrading of the road in its existing path (and at considerable costs) and a new outline plan for the town. Unlike other exhibitions in the Local series, De Vries does not merely voice a critical opinion, but goes further to suggest a planning alternative to the existing road, an alternative she calls “the pale blue bridge.” Turning the coastal highway to a bridge near Jisr would finally create broad, respectable access to the town, which would quickly be upgraded to city status. Furthermore, the bridge would also liberate the area’s water-rich nature from pollution, and would allow hikers to visit that currently-inaccessible part of Israel’s National Trail. De Vries’s plan does not interfere with nature reserves, producing areas, or expansions planned for other towns. Instead, it curves opposite to its current path, and adds jointly-owned infertile lands to Jisr’s territory, lands currently flooded each winter. De Vries therefore aims to allow Jisr to expand eastwards and develop its own unique residential area alongside a controlled swamp.

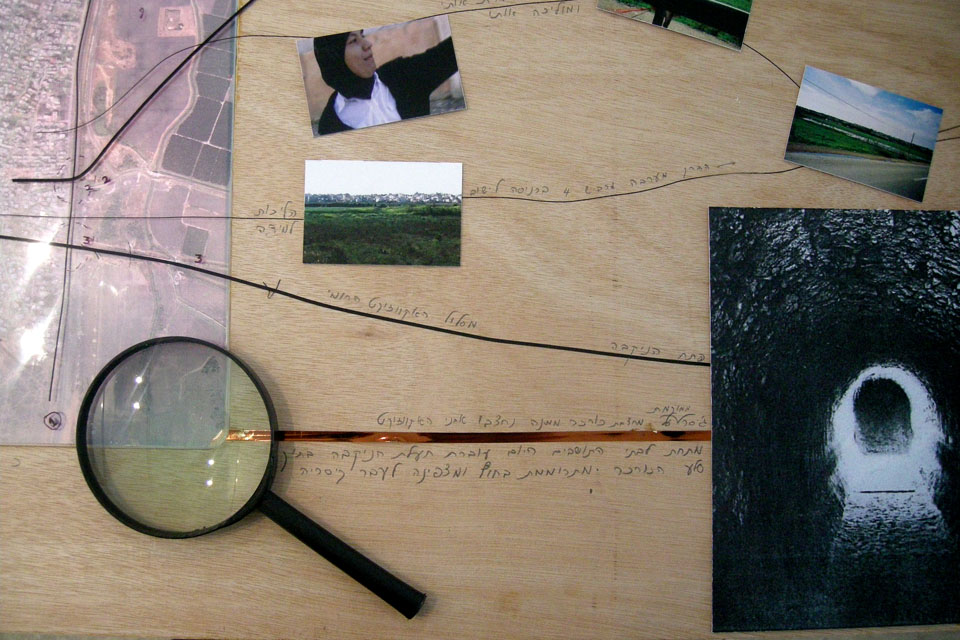

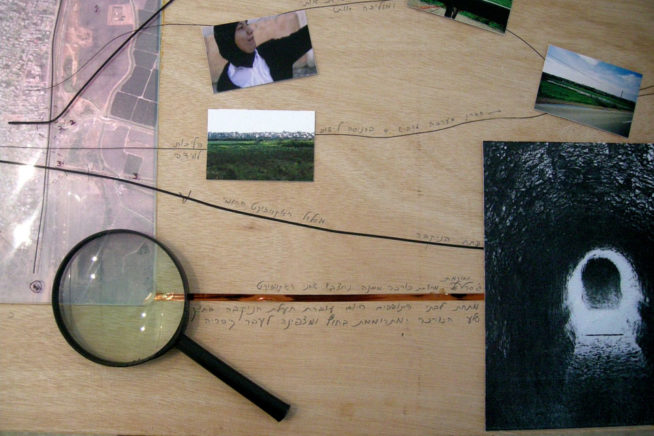

De Vries lays its arguments one by one on the exhibition table: here is the narrow access point; look how close the bus is to residential houses; note the density of the houses; see how the swamp appears each winter; please listen to the father whose son and daughter were killed on the road (the video artwork projected on the table); walk with me and the village women, and hear the difficulties they experience every day, moving in and out of the town. Can you not recognize a wrong when you see one?

De Vries appeals to our fairness and common sense. She believes that enlightened planning can solve problems, amend wrongs, and develop environmental possibilities to benefit all. Her suggestion foreshadows the transformation of Jisr from a poverty-stricken ghetto to an ecological center run by its residents.