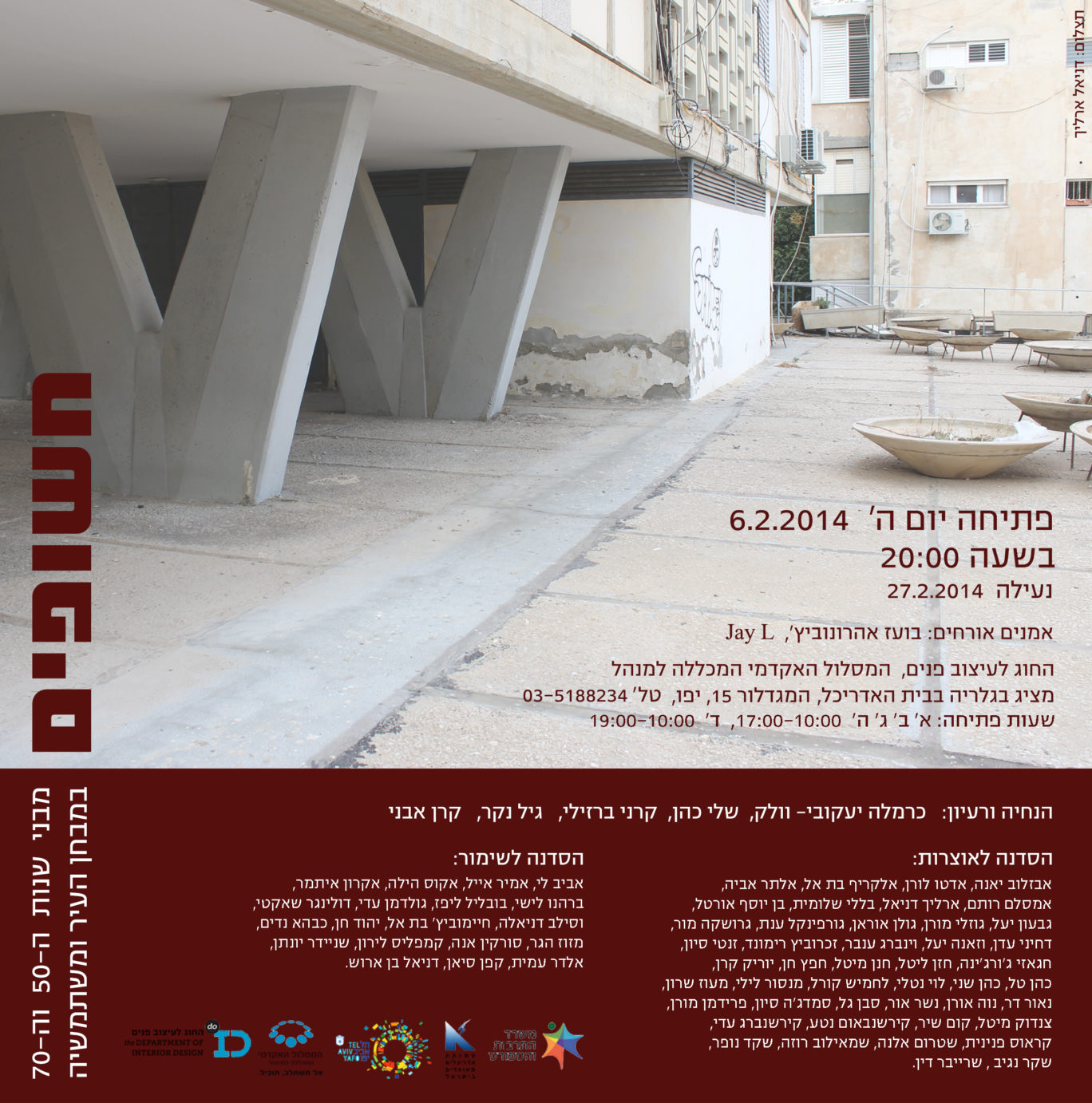

The Exposed exhibition at the Architect’s House Gallery is centered around eight different buildings built in Tel-Aviv in the late 1950’s through the 1970’s. The term “exposed” refers first and foremost to the poetics of the buildings’ construction style and material. Several buildings are brutalist structures, made of raw concrete, while others are functional structures without plastering or decorations. But in addition to these materialistic aspect, the term “exposed” also refers to the unmitigated, harsh manner in which the structures meet their occupants, tenants, and various marketplace agents such as workers, renters, traders, customers, and others. The featured buildings were constructed along main roads, and most were planned by leading Israeli architects. These buildings did not become isolated architectural icons, however, but instead managed to become an integral part of a busy urban center. This is highly idiomatic of Tel-Aviv’s historical urban center: small in stature, these and similar buildings accommodate various uses: offices and commerce (such as Beit Yachin and in El-Al House); culture combined with commerce, or residential buildings built as part of the main street (such as the Beit Lessin theater and the London Ministore). All this, without necessitating any pre-designated, closed areas.

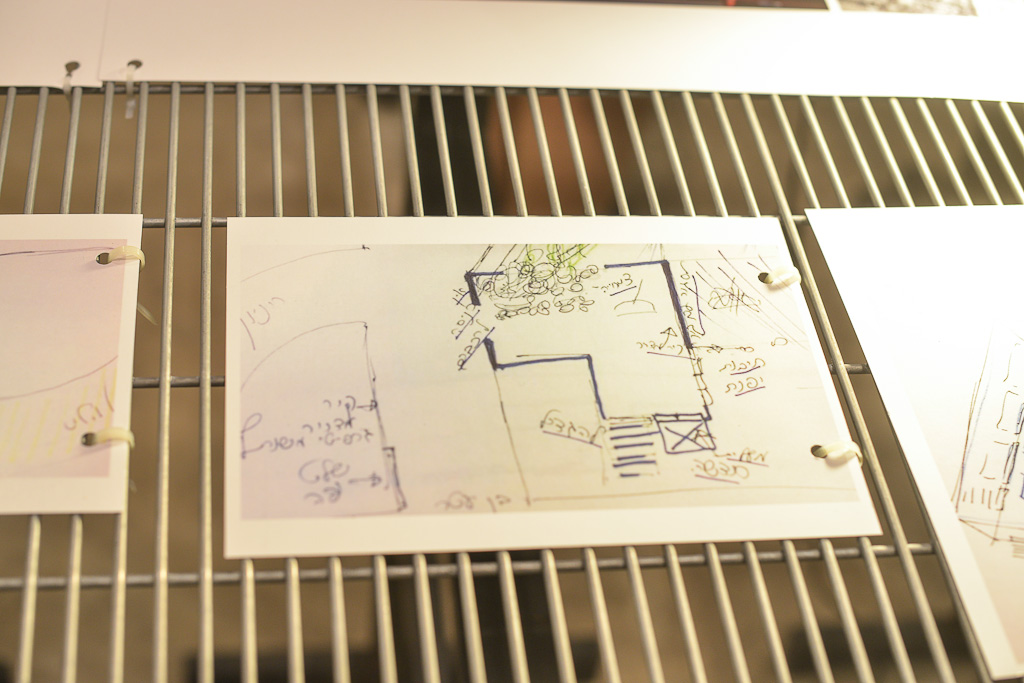

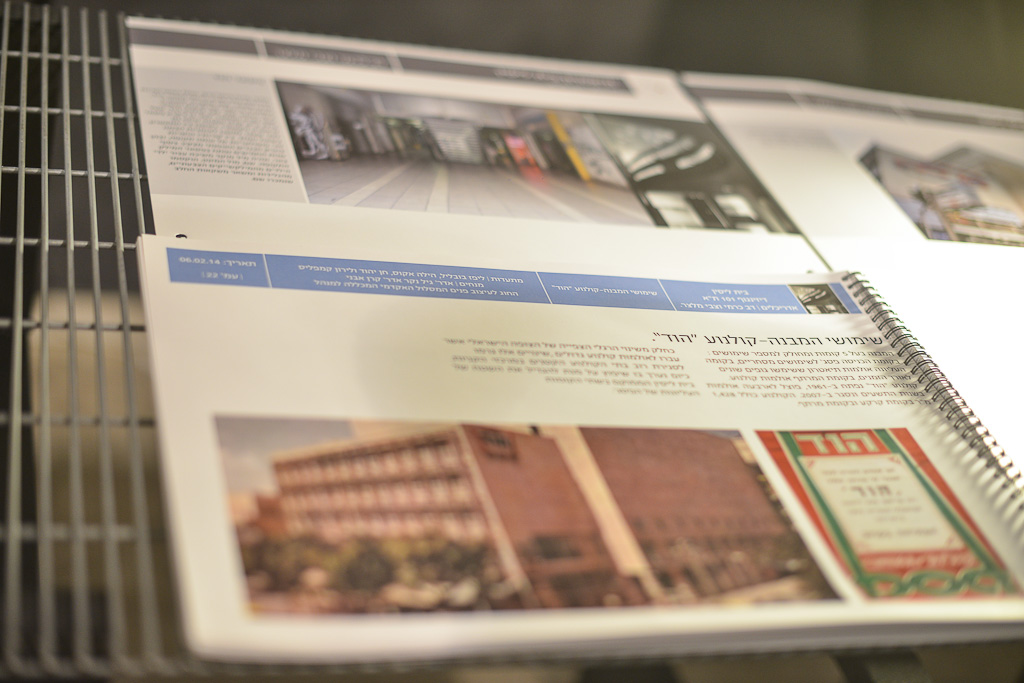

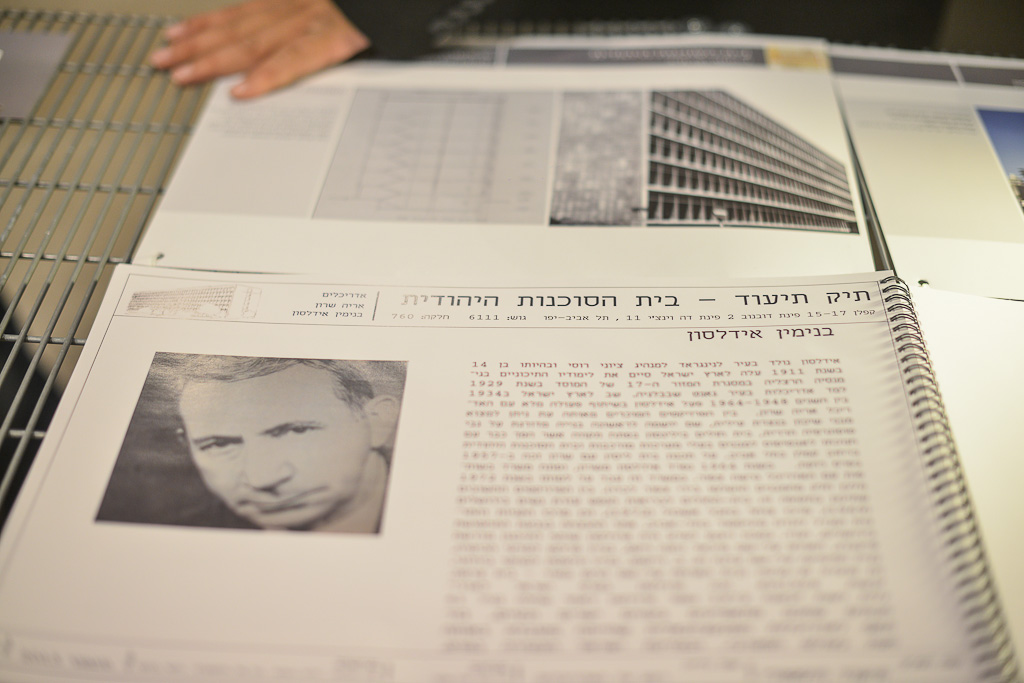

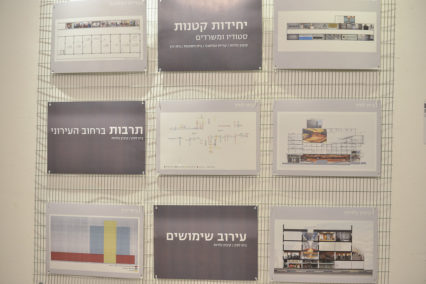

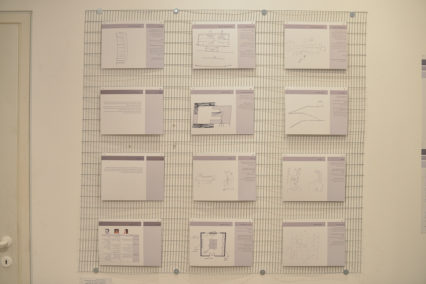

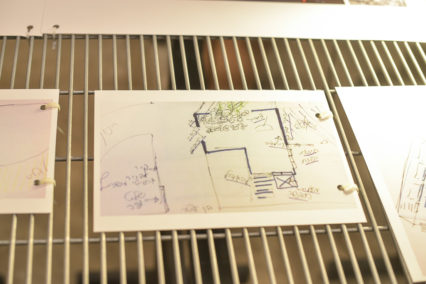

Market conditions have dictated the buildings’ transformation throughout the years: buildings originally set up as public institutions (such as the Agency House, Beit Yachin and El-Al House), are now used by small private businesses, sometimes following the privatization of their previous owners. And workshops of raw character (such as Kiryat HaMelacha and Kibbutz Galuyot 45) are currently being transformed in to small artist studios. Students from the preservation workshop have browsed through archives, interviewed architects, entrepreneurs, and building supervisors, and created computerized models for each building. Thus, their preservation files contain historical documentation of the buildings and their surroundings, as well analyses by building type, construction technology, architectural innovation, historical alterations, and possible future uses. Students from the curating workshop examined whether the buildings can withstand the test of time. They used situational tools to map the buildings, and made several intuitive, irregular visits. They present a visual documentation and analysis of the buildings’ urban context, in addition to video footage of their various users. They interviewed renters and employees, and asked them to draw mental maps to visually depict their daily experiences in these structures. Conversations with employees who spend most of their days there have shown that even the café waitress and the security guard have their own formulated opinions of the building’s architecture. Together with depicting the buildings’ urban and architectural advantages, the exhibition also includes photos and videos of their neglected, darker sides: an unwelcoming approach to the Tsavta hall; a neglected commercial space in the former Hod covered passage, in Beit Lessin; and a deserted plaza overlooking Ben-Yehuda St., above the Shufersal building, which misses an extraordinary opportunity for a view of the street from a middle level.

Two former artisan shops, in Kiryat Hamelacha and Kibbutz Galuyot 45, have now become studio and exhibition spaces. They both appear in several photographs by two guest artists: Boaz Aharonovich documents the dark nightlife outside his Kiryat Hamelacha studio window. A commercial area by day, it becomes an arena of crime and prostitution by night. Similarly, artist Jay L. documented dancer Dafna Noy in a Kibbutz Galuyot 45 exhibit called “breathing concrete.” His photographs allow a symbolic reading of the connection between the city’s raw architectural elements and their inhabitants.

The exhibition is therefore a multifaceted view of the raw buildings. Alongside architectural values and urban vitality, the exhibition also explores their architectural flaws as well as darker, less appealing aspects. All these elements are discussed using terms like reuse and mixed use, as well as the future of brutalist architecture in the West.